This blog is a translation of my article that’s published by the Dutch Microsoft .NET Magazine (http://www.dotnetmag.nl/Artikel/2683/Unit-testen,-hemel-of-hel)

Unit Testing is a practice of which we are all convinced that it’s a good thing. I’ve seen many teams that start out very enthusiastic with Unit Testing, but in practice it’s often disappointing.

Tests are time consuming to maintain, slow running and sometimes it’s just hard to get some code under test. For these and other reasons, Unit Testing is a practice, that when under pressure slowly fades into the background. Even when we’re on paper convinced that Unit Testing offers advantages.

In this blog I’ll discuss some errors that often cause problems and some best practices how we can tackle these.

What exactly is a Unit Test

Many of the problems that teams encounter when using Unit Testing, arise in the definition of what exactly is a Unit Test. A Unit Test is all about testing the smallest possible piece of code to see if it meets the requirements. A Unit Test that uses a WCF service and talks to a real database is not a Unit Test.

Most of the time the Unit Test we write are not about ‘the smallest possible’. Problems such as tests that take way too much time to run, which for various indeterminable reasons just go wrong or that require constant maintenance with every code change all have to do with the failure to test the smallest possible piece of code.

We can compare this to the development of a car. You could get the whole car designed, build and then test it in its entirety. But what if the car won’t start, then what’s wrong? The battery, the motor or the wiring between them? Wouldn’t it be better to test the parts separately? Is the battery functional? If the engine gets no fuel, does it turn off? If you are confident that all components work separately and are tested then you can be much more comfortable when you assemble the entire car. If it starts and you can drive it to the parking lot you are pretty sure everything is working.

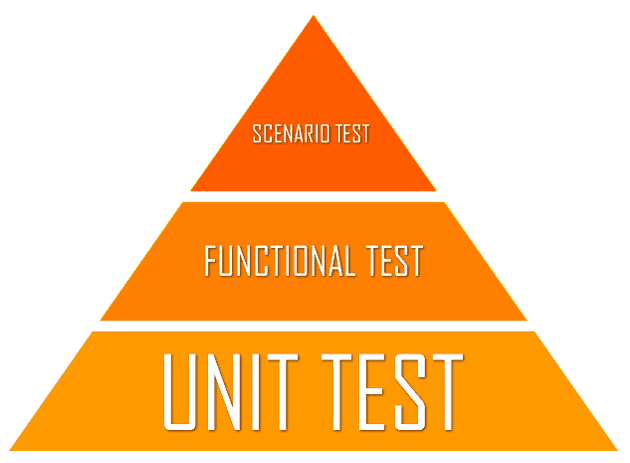

This shows that besides the Unit Tests, you also need to test larger blocks of code or even an entire application. Then we’re talking about Functional Tests and Scenario Tests. As the picture shows, there are in a lot of Unit Tests, some Functional Tests and eventually only a small number of Scenario Test

Good Unit Tests thus provide the basis for a high quality, stable product.

But what’s so difficult about writing a Unit Test

Writing a Unit Test is really not that difficult. Writing good testable code, however, is much more difficult and that’s where most of our problems come from.

But how can you make sure that your application can be tested as lot of small, individual parts and why does this often go wrong?

The development of an alarm clock radio

As an example, in this blog I’ll look at developing the software for a simple alarm clock that uses a service that retrieves the current time from a satellite. The hardware vendor has provided us with the following wrapper code:

public class HardwareClient

{

public TimeSpan DisplayTime { get; set; } public List<TimeSpan> CurrentAlarms { get; set; } public void StartAlarm()

{ ... }

public void StopAlarm()

{ .... }

}

public class SatelliteSyncService

{

public TimeSpan GetTime()

{ .... }

}

A first attempt for creating our Alarm Clock looks like the following:

public class AlarmClock

{ public AlarmClock()

{

SatelliteSyncService = new SatelliteSyncService();

HardwareClient = new HardwareClient();

} public void Execute()

{

HardwareClient.DisplayTime = SatelliteSyncService.GetTime(); // Check for active alarms // ....

}

}

It’s now easy to create an Alarm Clock and use it. But how would you test this code?

If we look at the definition of a Unit Test, we see that it’s about testing the smallest possible piece of code. If we now test our alarm clock, then we’re also testing the Hardware Client and the Satellite Sync Service. Is that test the smallest possible piece of code?

Suppose we want to test whether the alarm we have set really triggers. Maybe we start with creating an alarm that’s one second into the future. In our test we have to wait until that moment passes and then we have to find out how to check with the Hardware Client if the alarm was triggered.

Mocking and Dependency Injection

It would be a lot easier if we could control all the different parts that are used by our alarm clock and test them in isolation.

What if we would replace the AlarmClock with the following:

public AlarmClock(IHardwareClient hardwareClient, ISatelliteSyncService satelliteSyncService)

{

SatelliteSyncService = satelliteSyncService;

HardwareClient = hardwareClient;

}

There are two important changes. Instead of working with concrete classes, we work with an interface. In addition, the class now clearly states what he needs and gives us a logical seam where we can control this.

This demonstrates an important point when writing code that is easy to test:

The task of a class is to implement business logic, it’s not his job to create all kinds of objects. Look therefore whether the use of the new operator (or static data or singletons) in a class really belongs there together with business logic. Or should you move the construction logic outside the class? Make sure that you have seams in your code so you can replace a dependency in your a unit test.

In our unit test we now have the ability to replace IHardwareClient and ISatelliteSyncService with a more testable version. We can do this by creating a Mock. A Mock is an object that can be used in place of a real object and of which the behavior can be fully controlled. There are several frameworks that we can use to create Mocks. A well known mocking framework is Rhino Mocks. You can easily install it as a NuGet package.

Using Rhino Mocks we can create a new clock radio in the following manner and test it:

[TestMethod]

public void TestThatTheAlarmClockShowsTheTimeWhenExecuted()

{

// Arange

TimeSpan currentTime = new TimeSpan(0, 0, 1);

IHardwareClient hardwareClientMock = MockRepository.GenerateMock<IHardwareClient>();

ISatelliteSyncService satelliteSyncServiceMock = MockRepository.GenerateMock<ISatelliteSyncService

hardwareClientMock.Stub(h => h.DisplayTime).PropertyBehavior();

satelliteSyncServiceMock.Stub(s => s.GetTime()).Return(currentTime);

// Act

AlarmClock clock = new AlarmClock(hardwareClientMock,

satelliteSyncServiceMock);

clock.Execute();

// Assert

Assert.AreEqual(currentTime, hardwareClientMock.DisplayTime);

}

Of course you have to choose for each specific situation if you want to pass the dependency in the constructor or only to a specific method.

When setting a new alarm, the ISatelliteSyncService is not used . Therefore, in this case we can pass null for the ISatelliteSyncService . If someone else reads this test, this gives a strong message. He can be sure that if there is a problem with the code, this has nothing to do with ISatelliteSyncService.

[TestMethod]

public void TestThatWhenIAddAnAlarmItShowsUpInMyAlarmList()

{

// Arrange

IHardwareClient hardwareClientMock = MockRepository.GenerateMock<IHardwareClient>();

hardwareClientMock.Stub(h => h.CurrentAlarms).PropertyBehavior();

// Act

AlarmClock clock = new AlarmClock(hardwareClientMock, null);

clock.AddAlarm(new TimeSpan(0, 0, 0));

// Assert

Assert.AreEqual(1, hardwareClientMock.CurrentAlarms.Count;

Assert.AreEqual(new TimeSpan(0, 0, 0), hardwareClientMock.CurrentAlarms[0]);

}

The Law of Demeter

Suppose you’re at the checkout and the cashier asks you for twenty euros. Would you give your wallet to the cashier so they can get the money out or do you take the money out of your wallet and give only the twenty euro?

Probably we would all choose to give only the money. But when writing code, we make this mistake quite often. Do you sometimes pass a Customer object to a function, just to get the shipping address or a Factory which is then only used to construct something else?

Instead of having to create a complete customer with all the little details, we actually only need to pass an address.

This principle is called the Law of Demeter. Your code should only talk to his immediate friends, not against foreigners. So only pass the data that a function really needs. This in turn ensures better testable code with fewer links to other parts.

Generating test data

Another problem with writing unit tests is the test data that we need. Often this test data can be complicated to construct, which in turn makes a test very long and difficult to read.

Consider the following initialization code to test whether the price of an invoice is written to the database.

Address billingAddress =

new Address("Stationsweg 1","Groningen", "Nederland", "9726AE");

Address shippingAddress = new Address("Aweg 1", "Groningen", "Nederland", "9726AB");

Customer customer = new Customer(99, "Piet", "Klaassens", 30, billingAddress, shippingAddress);

Product product = new Product(88, "Table", 19.99);

Invoice invoice = new Invoice(customer);

What exactly are the important details in this? Is it important that the shipping and billing address differ? Is it the name of the customer? In a situation like this we can of course take a pretty good guess about what’s important or we could have a look at the code to figure it out. But consider the following initialization code:

Invoice invoice = Builder<Invoice>.CreateNew()

.With(i => i.Product = Builder<Product>.CreateNew()

.With(p => p.Price = 19.99)

.Build())

.Build();

The only detail which is mentioned here is the price. All other required data is automatically filled with dummy data. Besides readability, this has another advantage. If there is any changes to the Invoic, Customer, Product, or Address class that has nothing to do with the price, we don’t have to make maintenance changes to this unit test. The Builder Pattern can save us a lot of time as a project grows.

Conclusion

Unit Testing is a practice with a lot of potential. As developers, however, we must remain committed to writing better testable code. Then Unit Testing will pay of and we will have the advantage that better testable code leads to better code and fewer bugs.